Case Report

Case Study: Importance of Timely Diagnosis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Child with Vague Symptoms: Part 1

Atefeh Samadi-niya*

IRACA Solutions Inc, Canada

*Corresponding author: Atefeh Samadi-niya, IRACA Solutions Inc, 1096 Bancroft Drive, Mississauga, Ontario, L5V 1B9 Canada

Published: 30 Aug, 2016

Cite this article as: Samadi-niya A. Case Study: Importance

of Timely Diagnosis of Non-Alcoholic

Fatty Liver Disease in a Child with

Vague Symptoms: Part 1. Ann Clin

Case Rep. 2016; 1: 1111.

Abstract

Introduction: This article describes complications of misdiagnosed Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver

Disease in an 8-year-old overweight child presented to Emergency Room due to vomiting and

severe epigastric pain. The child complained of headache, shortness of breath during physical

activities, tiredness, pressure on heart, and increased waist circumference for few months before

visiting hospital.

Materials and Methods: Initial assessments were completed by an Emergency Room physician, a

family physician, and a hepatologist in early 2016. Further assessments will be reported in follow-up

articles.

Results: The child who was misdiagnosed for indigestion or gastritis, due to family history of

positive H-pylori in his father, was found to have extremely high level of Liver Function Tests,

hepatomegaly, dyslipidemia, constipation, bloating, and a diet full of junk food. Based on the initial

assessments and referral to hepatologist, NAFLD is reported as the initial diagnosis.

Conclusion: Considering increasing prevalence of NAFLD in children, routine screening of

overweight and obese children for possibility of NAFLD is recommended so early interventions and

lifestyle changes can be implemented. Quality of life is affected a child with a large liver due to its

pressure on adjacent organs.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; Dyslipidemia; Obesity; Children; High liver functions; Hepatomegaly

Introduction

Hepatomegaly due to the Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease is prevalent in children of

industrial countries where children obesity is a public health issue as well as a primary care concern

[1]. Timely diagnosis of NAFLD in a child with vague symptoms could lead to prevention of

severe complications and chronic medical illnesses that are devastating in childhood and create

unnecessary expenditure for healthcare systems as they could cause chronic illnesses in adulthood

[2]. The concept of nourishment has been replaced by eating too much and not having a healthy

variety of foods suggested by the Nutrition Guides [3].

The Fatty Liver Disease can start as early as age four [4]. In fact, the childhood obesity rate has

increased in the past few decades and the timely diagnosis and correction of diet and lifestyle can save

lives, prevent chronic diseases, and save the healthcare budget [5,6]. The presence of hepatomegaly

due to Fatty Liver Disease should be considered a dire diagnosis that needs extreme attention and

continuous follow-up until the child is heathy again because the percentage of adolescents diagnosed

with the disease is increasing [7,8].

The NAFLD is asymptomatic until another medical condition accidentally reveals its presence

or leads to other consequences that are seen in this child who presented to the ER due to vomiting

and epigastric pain. The focus of this case report is on timely diagnosis and paying attention to

the possibility of misdiagnosis or late diagnosis of NAFLD. If healthcare care providers consider

NAFLD diagnosis in every cute, chubby, and possibly overweight child, early interventions can

change the course of treatment tremendously [9,10].

Case Presentation

The 8-year old overweight child presented to the emergency department with epigastric pain, vomiting and some strikes of blood in vomitus, which frightened the

family the most. He was assessed in the emergency department and

was kept under observation for few hours to rule out acute abdomen.

An X-ray of abdomen and a set of essential blood tests were ordered.

Past medical history

The family reported that the epigastric pain was repeated

frequently in the past few months but was interpreted for bloating

and extra gas in bowels and the urgent need for defecation. Each time

after defecation, the pain was lessened and the family assumed that

the pain was due to constipation. In addition, the family specified that

the child’s stool floated on the toilet water in the past few weeks. The

defecation had become extremely strenuous and the child had a very

large abdomen with extra bowel gas in his digestive system shown as

consistent passing of gas.

The child’s abdominal circumference began increasing in the

year previous to the Emergency Room visit and all the pants for

his age were too tight for him so size 18 pants (instead of size 8-10)

were purchased for this 8-year-old child. In the past few days before

arriving in the Emergency Room, severe epigastric pain and vomiting

were reported in the early morning but it was interpreted as extra

stomach acid. The child was complaining of heartache and showed

the left side of his chest as the pain was occurring. Very puzzling for

the family, the child complained of headaches, especially at night,

extreme sweating at night, tiredness, dry itchy skin, pain in the legs,

feeling of pressure on the heart, and shortness of breath. The child

became angry very often as he was being more sensitive than previous

months. He was also upset that his abdominal circumference had

increased tremendously and complained about it.

Family history

The family history of Gastroesophageal Reflux and Helicobacter Pylori in his father led to initial differential diagnosis of possible

gastritis due to excessive acid secretion. The family history showed

Diabetes in both paternal grandparents and in the child’s father. The

father was also diagnosed with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease,

received medication to lower lipids and glucose, and was advised to

reduce weight.

Results

At the time of arrival at the hospital, weight was 45 Kg and height

136 cm. Please note that Canadian Diabetes Foundation emphasizes

that the children and elderly have a lower muscle mass so the lower

level of Body Mass Index of 24.3 in the 8-year-old child would be

considered obesity rather than normal range shown in adults [11,12].

Diet and lifestyle

The diet of the child was assessed and was full of junk food and

no vegetable or fruit [3]. The child was inactive due to playing digital

video-games. Child left the swimming class due to shortness of breath

after the speed and endurance of swimming lessons increased.

Abdominal x-ray

The plain x-ray showed residues of stool in large bowel in different

locations despite routine daily defecation. No other abnormality was

reported.

Ultrasound

The ultrasound reported hepatomegaly filled with fat measured

17 cm horizontally and no other abnormalities [13].

Blood work-up

The initial set of blood tests revealed extremely high level of Liver

Function Tests (AST and ALT), which were about 10 times higher than the normal level [14-17]. The first set of laboratory tests are summarized in Table 1.

After ER visit, the child was followed up in the office and the

Family Physician requested Abdominal Ultrasound and complete

blood and urine lab tests including the test for Helicobacter Pylori.

The child was scheduled to visit Family Physician to check the weight

and general conditions every month after hospital visit for 6 months

[18-21]. Table 2 shows the additional tests results. The Complete

Blood Count (CBC) and Urine Analysis were reported as normal.

As Table 2 shows the level of both AST and ALT has decreased

comparing to Table 1. The level of cholesterol was very high too.

After a period of 2 months of healthy diet and complete defecation of

bowels, weight started decreasing [10]. Therefore, the modifications

in diet and exercise showed positive results in this child immediately

after intervention, which is promising [22].

Referral to the hepatologist

American Association of Family Practise has provided guidelines

for assessment of Fatty Liver Disease [15,23]. Further referral to

the Hepatologist located at a Gastroenterology and Liver clinic of

a children specialty hospital led to further tests Ruling out other

reasons led to initial diagnosis of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

at this time. Thyroid function was reported as normal [24,25]. Further

assessment will be performed and the results will be reported in

follow-up articles.

Discussion

The statistics show that 73% of overweight people develop simple

fatty liver and 23% of them develop inflamed fatty liver [7]. The

holiday tradition of extra sweets and treats became every day diet of an

8-year-old child. The patient reported caused an extremely dangerous

high level of Liver Function Tests, dyslipidemia, 17 cm hepatomegaly,

increased abdominal circumference, headache, extra sweating,

epigastric pain, leg pain, itchiness, tiredness, and an irritable mood

If this medical condition had been left untreated or undiagnosed, it

might have led to cirrhosis and loss of liver tissue [16].

In this child, the rise of AST was almost 10 times more than the

normal limit (Table 1). A stool softener was prescribed for the child

for 10 days to remove all the residues of stool in the bowel due to the

size of the liver. This size of the liver explained the pressure on the

heart (heartache), incomplete defecation and remained stool in large

bowel, pain in epigastric area due to pressure of liver on stomach, and

shortness of breath due to pressure on lungs [13]. Quality of life of

children with NAFLD is affected by the size of liver and its pressure

on the adjacent organs [26]. Besides, the ability of children to perform

physical activity is less than normal [27]. Comparison of tests showed

decreasing level of Liver Function Tests, which is promising and

show the positive effects of early intervention and change in lifestyle

and diet [10].

Timely Diagnosis of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a

child with vague symptoms can save lives. If physicians consider the

possibility of NAFLD in overweight children and include the routine

screening for hepatomegaly, Liver Function Tests, and Dyslipidemia

especially in families with high risk factors such as diabetes, the

cost of prevention and early intervention is less than cost of more

advanced assessments and treatment options for undiagnosed or

misdiagnosed cases of hepatomegaly due to NAFLD. Families should

receive information pamphlets from schools, community centers,

healthcare professionals regarding NAFLD.

Conclusion

After a few months of avoiding sweet, fatty, and junk food

in a child who was initially diagnosed with Non-Alcoholic Fatty

Liver Disease, this child is now putting on size 14 pants, have no

abdominal pain or heartache, headache, or extra sensitivity. His

family has chosen a liver-friendly diet full of green vegetables and

healthy fruits and has cut down on the amount of consumed fat and

sugar. He is now able and willing to participate in sport activities in

school, community centers, and started his swimming lessons and

competitive swimming. He shows more positive attitude toward

friends and family members, and laughs more often. The repeated

tests (Table 2) show improvement just by changing lifestyle and diet

of an 8-year-old. Further follow-up tests and additional assessment

will be reported in future articles and will provide a better long-term

picture of changes in liver function tests.

This case report emphasizes the possibility of presence of

extremely large size liver in children who complain of headache,

abdominal pain, and extreme tiredness. It is crucial to remember the

hepatomegaly and possibility of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

(NAFLD) in children as well. Considering an early abdominal

ultrasound plus the complete laboratory tests including Lipid Profile,

Liver Function Tests, Blood Glucose, Urinalysis can save lives.

Children’ obesity and NAFLD should be treated as public health

issues that lead to many chronic diseases during childhood and

adulthood. A simple clinical picture of indigestion, bloating, and

epigastric pain in overweight or obese children could be NAFLD with

hepatomegaly, which significantly decreases quality of life and could

lead to chronic illnesses in adulthood if left untreated. Additionally,

referrals to dietitian, correction of lifestyle, and follow-up visits are

recommended.

Acknowledgement

This article is written for the first and special issue of the Annals of Clinical Case Reports Journal, Family Medicine and Public Health, published by Remedy Publications Inc. as an open-access article in the upcoming inaugural edition. Special thank to all healthcare professionals who save patients in different healthcare organizations and healthcare administrators or managers who consider adequate amount of budget for necessary tests in children that prevent higher healthcare budget expenditure in adulthood. Thanks for the opportunity to share this case report with other colleagues.

Table 1

Table 2

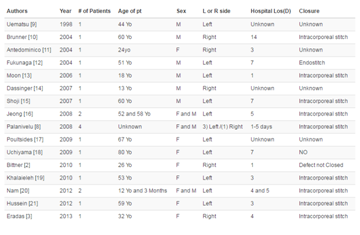

Discussion

Brain metastases are the most common cerebral tumours. The most common primary tumour sources are lung and breast [1-3]. Five to ten percent are from cutaneous melanoma [4]. The distribution of metastases closely follows the volume of the affected in the order cerebrum, cerebellum and brainstem [2] (approximately 10% [3]). In a large series of brain stem metastases [3] 9% were from melanoma. The most common symptoms were hemiparesis and cranial nerve palsies, with ataxia being uncommon. Ataxia is more likely to be a presentation of cerebellar metastases, but in this patient resulted from involvement of cerebellar connections.

References

- Anderson EL, Howe LD, Jones HE, Higgins JP, Lawlor DA, Fraser A. The Prevalence of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10: e0140908.

- Eklioglu B, Atabek M, Akyürek N, Alp H. Assessment of Cardiovascular Parameters in Obese Children and Adolescents with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2015; 7: 222-227.

- Health Canada. Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. 2012.

- Ovchinsky N, Lavine JE. A critical appraisal of advances in pediatric nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2012; 32: 317-324.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Health. Aim for a healthy weight, children and teens. 2016.

- Loomba R, Sirlin CB, Schwimmer JB, Lavine JE. Advances in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009; 50: 1282-1293.

- Canadian Liver Foundation. Fatty Liver Disease. 2015.

- Denzer C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children and adolescents. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz. 2013; 56: 517-527.

- Nobili V, Manco M, Raponi M, Marcellini M. Case management in children affected by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007; 43: 414.

- Wang CL, Liang L, Fu JF, Zou CC, Hong F, Xue JZ, et al. Effect of lifestyle intervention on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese obese children. World J Gastroenterol. 2008; 14: 1598-1602.

- Canadian Diabetes Association. How to calculate Body Mass Index. 2016.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Waist Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: report of WHO Expert Consultation. Geneva. 2011. 39.

- Wong VW, Chan HL. Non-invasive methods to determine the severity of NAFLD and NASH. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Practical Guide. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2013; 112-121.

- Rodríguez G, Gallego S, Breidenassel C, Moreno L, Gottrand F. Is liver transaminases assessment an appropriate tool for the screening of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in at risk obese children and adolescents? Nutricio´n Hospitalaria. 2010; 25: 712-717.

- Bayard M, Holt J, Boroughs E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am Fam Physician. 2006; 73: 1961-1968.

- Levene AP, Goldin RD. The epidemiology, pathogenesis and histopathology of fatty liver disease. Histopathology. 2012; 61: 141-152.

- Pong RW, DesMeules M, Heng D, Lagacé C, Guernsey JR, Kazanjian A, et al. Patterns of health services utilization in rural Canada. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2011; 31: 1-36.

- Cheung CR, Kelly DA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children. BMJ. 2011; 343: d4460.

- Koot B, van der Baan-Slootweg O, Tamminga-Smeulders C, Rijcken T, Korevaar J, Benninga M, et al. Lifestyle intervention for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: prospective cohort study of its efficacy and factors related to improvement. Arch Dis Child. 2011; 96: 669-674.

- Reinehr T, Schmidt C, Toschke AM, Andler W. Lifestyle intervention in obese children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: 2-year follow-up study. Arch Dis Child. 2009; 94: 437-442.

- Feldstein AE, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Treeprasertsuk S, Benson JT, Enders FB, Angulo P. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut. 2009; 58: 1538-1544.

- Fischer R, Shneider B. Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: swim at your own risk. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009; 10: 1-4.

- Schwimmer J, Newton K, Awai H, Choi L, Garcia M, Fontanesi J, et al. Paediatric gastroenterology evaluation of overweight and obese children referred from primary care for suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 38: 1267-1277.

- Bilgin H, Pirgon Ö. Thyroid function in obese children with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2014; 6: 152-157.

- Torun E, Özgen IT, Gökçe S, Aydın S, Cesur Y. Thyroid hormone levels in obese children and adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2014; 6: 34-39.

- Kistler KD, Molleston J, Unalp A, Abrams SH, Behling C, Schwimmer JB; Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN). Symptoms and quality of life in obese children and adolescents with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 31: 396-406.

- Manco M, Giordano U, Turchetta A, Fruhwirth R, Ancinelli M, Marcellini M, et al. Insulin resistance and exercise capacity in male children and adolescents with non-alcholic fatty liver disease. Acta Diabetol. 2009; 46: 97-104.